How can you achieve exponential improvements?

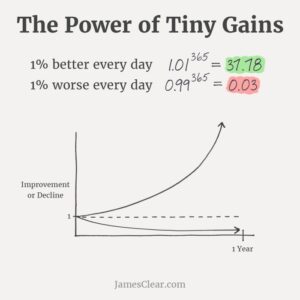

The secret lies in the formula for compound interest: improve by 1% every day, and by the end of the year, you’ll be 37.78% better.

Look at this graph if you want to convince yourself of what I’m saying:

Convinced? Sadly, this is wrong.

I’ve seen many people share this formula in self-improvement communities.

The idea sounds good in theory. I understand it’s a simplification to exemplify the concept more easily. But I believe this simplification doesn’t help; in fact, it can be harmful.

The flaws of compound growth in personal development

The first problem is that it assumes that skills grow at a compound rate, not a simple one. Every day you build on the progress of the previous day. If you’re learning to play the guitar, for example, it suggests that the learning on day two is based on that of day one, and so on for a year. But in reality, learning doesn’t always occur in this sequential way. Sometimes, what you learn one day has no relation to what you learned the day before.

Second, this theory doesn’t consider growth limitations. Imagine that you lift weights and want to be 1% stronger every day. That would be a spectacular improvement, but you would eventually reach a limit. You can’t infinitely increase the weight you lift by a compounded 1%. We have physical limitations that make this exponential growth impossible.

Third, the formula assumes a one-way growth path. If a marketer changes industries or specializes, are they better or worse than a year ago? If a writer learns to outline the topics of their articles faster, how much % have you improved that day? And if the next day you dedicate yourself to improving your vocabulary, is the % growth compounded from the previous day? If you change course, it’s complicated to evaluate your progress compared to the past. You’re on a completely different path.

The fourth problem lies in that you can’t certainly measure whether you’re improving or not. We use proxies or indirect indicators to approximate reality. Lifting more weight, for example, doesn’t necessarily mean you’re better. Maybe you have a poor technique that will end up hurting you in the long run. This is much more evident in areas like writing. What does it mean to be a better writer? Does it mean you write more words? Or that you have more followers? Does it mean you understand your clients’ requirements better? Does receiving an award make you a better writer? Awards, word counts, number of followers… these are all proxies.

Lastly, improving your skills doesn’t guarantee better results. Many measure their “improvement” based on results, often economic ones (I earn more money in my job, therefore I must be better than before). But this is a fallacy. Luck and other external factors greatly influence the final outcome. There are things you’ll do that simply won’t turn out the way you want, no matter how hard you try.

Don’t misunderstand, I believe in continuous improvement. But we are much more than a simple formula. Personal improvement is a complex path that can’t be simplified into a compound growth formula.